Kendra Ramsey and Laura McCamy of CalBike and Laura Tolkoff from SPUR also contributed to this article.

As our state heats up (literally), some of the most effective infrastructure for fighting climate change has been under siege. The governor cut $400 million from the Active Transportation Program (ATP) but made no corresponding cuts to money designated for building climate-killing freeways. Caltrans has negotiated changes that dilute the Complete Streets Bill, S.B. 960, reducing the likelihood that the agency will give people biking, walking, and taking transit equal weight with the needs of people driving cars.

That’s a problem. Caltrans has a history of failing to follow its own policies around Complete Streets. CalBike has spent the last several months reviewing Caltrans Project Implementation Documents (PIDs) it received under the California Public Records Act for projects since the governor vetoed S.B. 127 (the prior Complete Streets bill) in 2019 and since Caltrans updated its Complete Streets policy, DP-37. Our review has found patterns of downgrading and eliminating Complete Streets facilities in road repair projects. We also gathered survey responses about user experience on state routes that double as local streets and reviewed crash data.

We plan to release our full report, Incomplete Streets: Caltrans Fails to Protect Vulnerable Road Users, in August. In the meantime, we will publish a series of excerpts from our research, starting with an example of Caltrans shortchanging pedestrians and doing the bare minimum for vulnerable road users.

Counting ADA Implementation as Complete Streets in District 3

Caltrans consistently counts federally required ADA implementation as a Complete Street facility to meet its performance targets. However, ADA implementation is not an optional street improvement. Federal regulations require ADA upgrades during repaving projects, so Caltrans has no choice but to include these elements.

It’s often very clear when pedestrian facilities are legally required and when they are not. When implementing ADA requirements, Caltrans consistently misses the opportunity to make wholescale safety improvements when rehabilitating the entirety of the right-of-way. Caltrans will often shortchange pedestrians while keeping drivers safe and giving them full accessibility.

One such example (among dozens) is a 21.5-mile repaving project in the 2022 State Highway Operation and Protection Program (SHOPP) on SR 32, a two-lane arterial in Glenn County between Interstate 5 and the Sacramento Bridge. This route was identified as having significant pedestrian needs. The elements Caltrans proposed include constructing new sidewalks to close gaps, converting non-compliant driveways, relocating non-compliant pedestrian walk buttons, adding ADA curb cuts, and making other ADA fixes. It estimated $893,500 for the required fixes in a $20.7 million project, including $286,500 for 149 ADA curb ramps.

The final project included 104 ADA ramps at a cost of $188,000. The remaining curb ramps and the rest of the pedestrian improvements were pushed to an unplanned Phase 2 of the project.

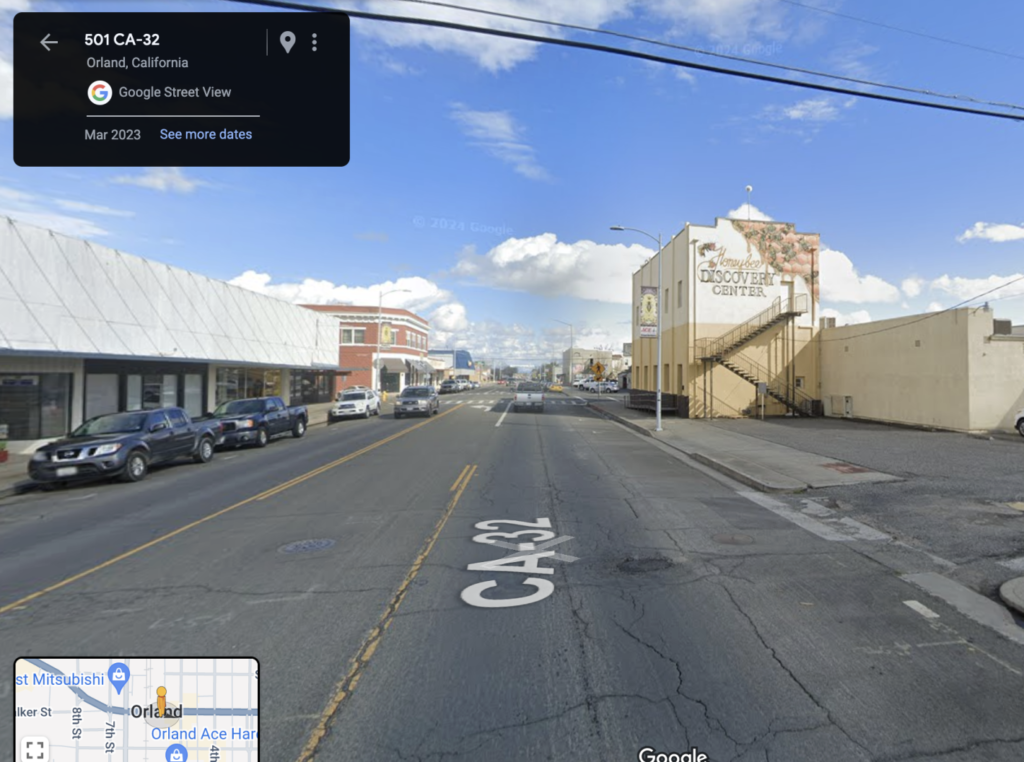

A view of this stretch of state roadway on Google Street View shows a main route through the city of Orland, with speed limits of 30 mph in town and as high as 55 mph where it enters a more rural section of the county. There are no bicycle facilities, except a short segment of Class II (painted) bike lane between a through lane and a right turn pocket onto Papst Avenue. The sidewalk and driveway quality varies, with many missing curb cuts, areas of crumbling pavement, and segments where the sidewalk disappears altogether. In addition, the street has numerous uncontrolled intersections and missing or substandard crosswalks.

This is, in short, a segment of roadway that would benefit greatly from a thorough Complete Streets treatment. Instead, Caltrans will build fresh, smooth pavement for the vehicular portion of the street while leaving many of the areas used by pedestrians to crumble — an apt image of the regard the agency has for each constituency and the have/have not experience of drivers versus people walking and biking on our state roadways.

Caltrans cited SHOPP funding limitations and suggested that the City of Orland apply for ATP funding to complete the needed pedestrian improvements. See pages 202-206 of the PID for details.

The 2022 SHOPP had a budget of $17.9 billion. The chronically underfunded Active Transportation Program approved $1.6 billion in grants over the four-year Cycle 6 in 2023 because of a one-time general fund contribution of $1 billion, which the governor tried to claw back in the succeeding two budget years.

The ATP normally gives about $500 million in grants every two years. Because of budget cuts, Cycle 7 in 2025 will have just $200 million. Yet Caltrans cries poor in its SHOPP budget, refusing to spend a fraction of the money it allocates to paving car lanes on improvements for people walking and biking and pushing projects to the ATP, which is chronically underfunded and oversubscribed.

Pattern and Practice at Caltrans District 3

While all Caltrans districts are now required to have a Complete Streets Coordinator on staff, some districts do a better job of honestly serving the needs of vulnerable road users than others. District 3 covers eleven counties in Central Valley, Northern California, and the Sierras: Sacramento, Yolo, Colusa, Glenn, Nevada, Butte, Sutter, El Dorado, Placer, Sutter, and Sierra. It is not known for adhering to headquarters’ guidance on Complete Streets, as shown in the SR 32 Orland example above. The rationale for doing less on that project is typical for this Caltrans district.

District 3 is perhaps best known as the district pushing through the Yolo Causeway highway expansion project. That project, which has been approved despite internal and external opposition, led to the firing of Caltrans Deputy Director Jeanie Ward-Waller after she blew the whistle on improper use of funds for freeway widening and insufficient environmental review.

How to Fix Potholes — and the Climate

We know what we need to do to zero out transportation emissions. Converting to EVs and powering them with renewable energy is part of the puzzle, but it’s not enough. We need to give Californians true transportation choices rather than forcing most people to get around by car. That means creating infrastructure like protected intersections, bus boarding islands, and connected bikeways that make active transportation easy, convenient, safe, and appealing.

California cities are clamoring to add Complete Streets to their neighborhoods. Lack of adequate funding is one obstacle to progress. Caltrans, which maintains many state routes that serve as community main streets, is another. The agency is often careless with the lives of people biking and walking when it builds dangerous interchanges and slow to change when it has the opportunity to make a corridor more welcoming to people who aren’t in cars.

We don’t suggest that Caltrans hasn’t changed; it has. However, agency and district leadership still continue the dangerous practice of ignoring Caltrans’ own policies when it comes to vulnerable road users.

Some projects and some Caltrans districts stand out for incorporating Complete Streets into roadway repair, and the documents Caltrans provided to CalBike included some projects designed solely for the benefit of active transportation safety. However, we still found many Caltrans projects where bicycle and pedestrian needs were ignored and the recommended Complete Streets elements were downgraded, often to the point of providing no real safety at all.

Next in our series: An Orange County boulevard with a history of crashes.