In an election season that has been dominated by discussion of development, traffic, and the relationship between the two, precious little time has been spent on the deadly cost of car-culture measured in the loss of human lives.

In fact, when long-time safety advocate and City Council candidate Richard McKinnon discusses Vision Zero, the world-famous Swedish transportation program that is saving lives in Europe and the United States, he is either ignored by the local press or mocked as a “Unicorn chaser” by a local crank, who for some reason has a column in the Daily Press.

Vision Zero is not a local curiosity, but an international movement towards safer streets that began in Sweden in the 1970s.

At the time, Sweden decided that the number of traffic deaths were too many, so it began to base every transportation design, construction, and enforcement decision around a basic premise: “Will it help reduce Sweden’s total traffic deaths to zero?”

Today, cities around the world have adopted that question as the guiding principle for their enforcement and planning decisions. There is also usually a goal attached for when a city will achieve Vision Zero, i.e. when it will no longer have people dying as they move around the city either in a car, on the sidewalk, or in a bike lane.

For more on Vision Zero, read this op/ed I wrote for Streetsblog earlier this year.

Last week, I sat down with McKinnon to talk about what Santa Monica would need to do to truly embrace Vision Zero and make Santa Monica’s streets some of the safest in the world.

The answer wasn’t what I expected.

“The culture of this city is about moving cars around. Four, five, six people die every year, and there’s more dangerous interactions that must be stopped,” McKinnon began. “We need a culture change, a real shift in how we think about our streets. That’s a top-to-bottom change from the people in Planning, to the City Council, to the people trying to get from one part of the city to the other.”

However, in McKinnon’s mind, the process of making the city a safe place to move can’t only be a top-down movement. Too many well-meaning plans end up becoming political tempests because staff drives the process and other stakeholders feel left out and alienated from the process, he said.

So when I followed-up by asking what the first thing the City Council could do, McKinnon doesn’t start talking about the need to gather and present high quality data (which I’ve identified as a first step in previous pieces) but about starting a conversation between city government and residents.

“What happens when the City proposes these things is that people can resent them if we’re telling them what to do,” adds McKinnon. “You need to build a consensus. To do that you start at the Council, but you have to widen the discussion… Bring in the Council, the Planning Department. Get the cops to buy into it. Getting senior citizens to realize that this is a life-saving program for them.”

“All Santa Monica is about consensus and collaboration,” he said.

Getting buy-in from the police, who McKinnon praises as “some of the best in the world”, is probably the most crucial point from a long-term perspective. Lack of law enforcement involvement in New York and San Francisco has hamstrung the Vision Zero program. And McKinnon has a clear answer for what the SMPD could do immediately.

“The number one thing I would crack down on would be use of handheld devices. I’d have a blitz on them. I would have that blitz last months. It’s distracted driving,” he continues.

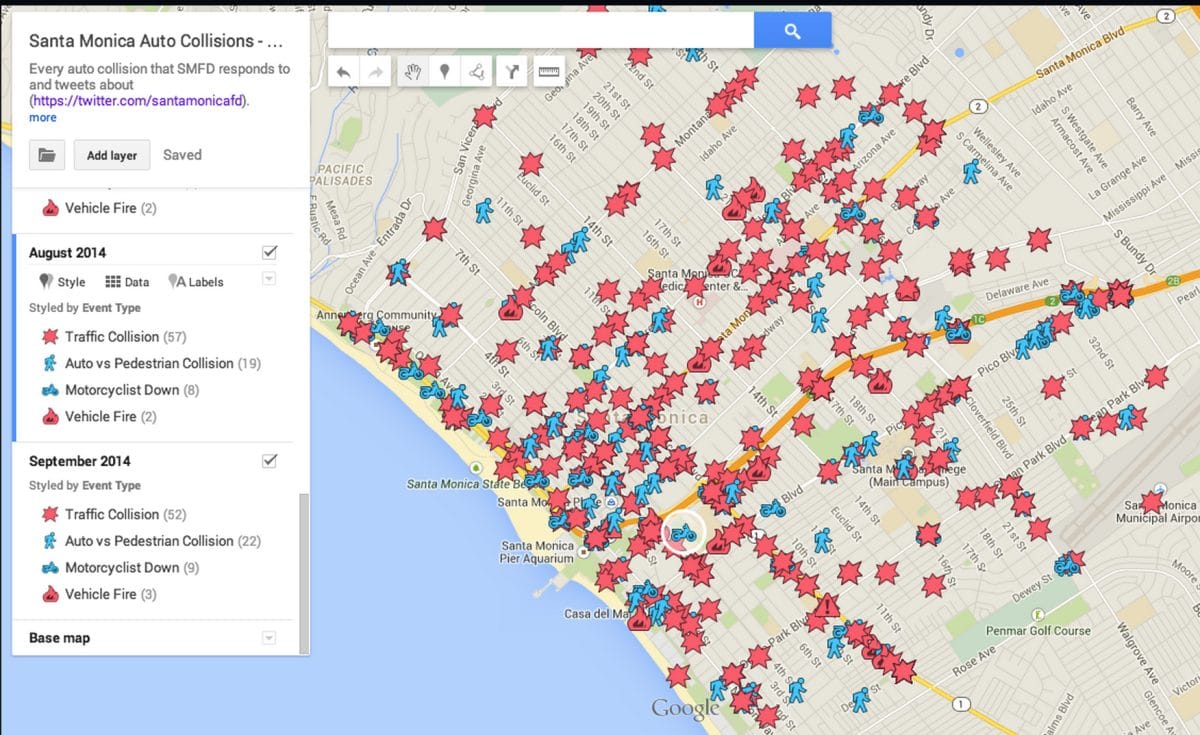

Which isn’t to say that good data isn’t important. The above map is put together by Adam “Danger Taco” Rakunas and is helpful, but is just a fraction of the information the City needs. Tracking crashes is a good start, but to develop a truly multi-modal Vision Zero plan, traffic density, bicycle and pedestrian counts, school and park location, transit stops (current and future), and more need to be included.

Median resident income level is also a useful data overlay to have to ensure that the best street improvements aren’t only focused in the highest-rent zip codes.

But even though creating safe streets is a priority for McKinnon, he recognizes that streets that are over-saturated with cars create mobility challenges for residents, especially graying seniors, who have found their trips across the city taking twice as long as they remember.

“One of the things you discover when you’re out door knocking is that older people really hate bikes. Once you explain to them why people feel afraid to ride on the road, they start to understand,” he replies. “Safety is a really important issue you can drive. Safety produces numbers and stats that make your argument for you.”

As for what City Planning can do, McKinnon wants to see more projects similar to the Michigan Avenue Neighborhood Greenway (MANGo), but also recognizes that the city has a mobility problem for people in cars.

“We need to figure out, there’s still a movement of cars problem. If you’re on one side of the city, how do you get to the other side of the city,” McKinnon argues. “The frustration of the population moving from one side of the city to the other. It used to be eight minutes to get across the city, now it’s 22…There’s a circulation issue.”

In the end, creating safe and livable streets should be the top priority of any 21st century city’s transportation program. In Santa Monica’s Council race, there’s not a lot that differentiates the candidates running on a “no-growth” or “slow-growth” platform in terms of their proposed policies, but prioritizing safety over vehicle speed is a platform that not many candidates have even tried to address.