Housing affordability in California is the worst it has been in the state’s history and it’s widening the gap between rich and poor, according to a report from the state’s Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) released Tuesday.

The draft report, which can be read in its entirety here, explains that cause of the affordability crisis is, in large part, a dire housing shortage and an overall failure of California cities to allow enough new housing growth to absorb growing demand.

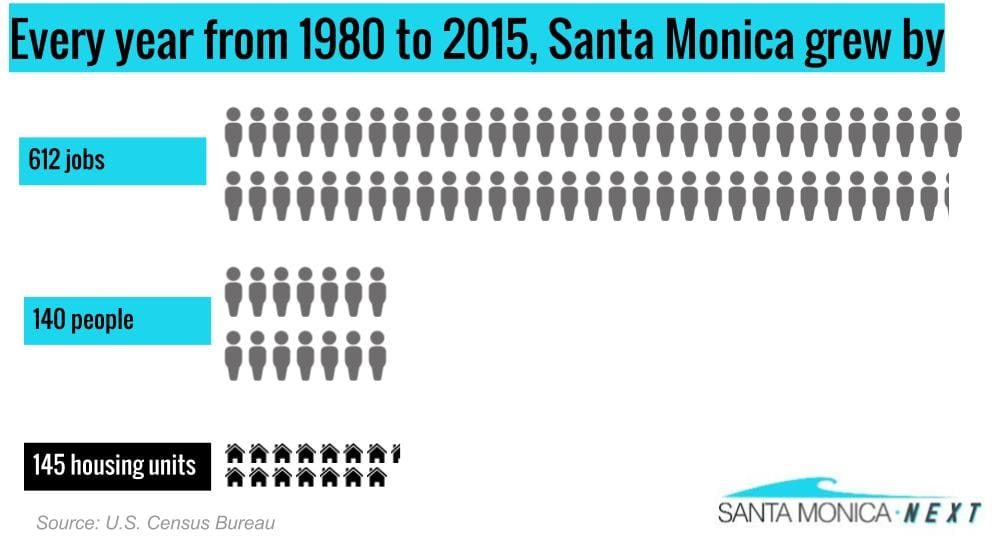

In Santa Monica, like other desirable coastal California cities, that has been true for decades and one major factor driving the need for more housing in places like Santa Monica and Los Angeles is job growth.

The nexus between job growth and the need for more housing is clear in other cities facing similar affordability problems. Probably the most extreme imbalance in California is in the Bay Area, where, since 2011 only about 94,000 housing units were permitted and about 531,000 jobs were created, according to an article in the San Francisco Chronicle from last April.

The HCD report notes that statewide, over the last decade, housing production has averaged only about 80,000 new units a year, “and ongoing production continues to fall far below the projected need of 180,000 homes annually.”

But new homes can’t simply be placed anywhere in the state. The places where the rents are rising the fastest — namely where the good jobs are — are in most dire need for more housing.

“Lack of supply and rising costs are compounding growing inequality and limiting advancement opportunities for younger Californians. Without intervention much of the housing growth is expected to overlap significantly with disadvantaged communities and areas with less job availability,” the report reads.

“Continued sprawl will decrease affordability and quality of life while increasing transportation costs,” according to the report.

In the Bay Area and in parts of the Los Angeles region, including Santa Monica, that imbalance has driven some of the highest rents in the country and contributed to growing inequality as lower and middle-income households are forced to live farther and farther afield from well-paying jobs and better schools. Sometimes, they are even leaving the state altogether.

In 2016, Santa Monica approved 380 new units. The vast majority of them, 318, were part of one project that took several years to negotiate and will likely take several more years before they come online. The project, 500 Broadway, included 249 market-rate units and 64 deed-restricted affordable units located a couple blocks away.

To get an idea how tough it is for renters in Santa Monica, it’s important to look at the rental vacancy rate.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS), over the last five years, the vacancy rate for rental units in the city has averaged about 2.8 percent, meaning that at any given time in the city less than three percent of rental units are on the market for new tenants. The rest are either occupied or have been taken off the market for other reasons.

By comparison, San Francisco’s vacancy rate in 2014 was 2.5 percent, Los Angeles’ was 3.4, and Detroit was 7.5, according to the ACS.

“Such a low vacancy rate tends to signal a very tight rental market, with high demand for apartments and more latitude for apartment owners to increase rents,” Andy Agle, Santa Monica’s director of housing and economic development, told Santa Monica Next in and interview last year.

“Anyone who has been in the rental market in Santa Monica recently has likely experienced the high demand and high rents,” he said. “The 2015 median market rent for a two-bedroom apartment built before 1979 was $2,750 per month. A household would need an annual income of $110,000 per year to afford the apartment without being burdened by the rent.” Burdened by rent is defined as spending more than a third of your income on rent.

Said Agle, “Rents for newer apartments are even higher and require even higher incomes to avoid rent burdens.”

In recent years, most of the new housing growth in Santa Monica has been in its transit-rich downtown. But it remains uncertain if, when the city adopts its updated Downtown Community Plan, the regulatory standards in the plan will continue to allow for moderate housing growth there.

Over the last several decades, Santa Monica has had no lack of opposition to new housing growth, even where new housing would not have displaced existing tenants. Most recently, anti-growth advocates placed Measure LV on the ballot, which would have required a city-wide vote on nearly all projects taller than 32 feet. Though it was soundly defeated, some on the Council are considering putting another, similar measure on the ballot in the future.

And in Los Angeles, Measure S, formerly known as the Neighborhood Integrity Initiative, threatens to halt much of the new housing growth happening there.

In short, the problem could get much worse.