Editor’s Note: This is part two of a series looking at the cost of renting in Santa Monica. Click here for part one.

When Charles and Carol Gasko moved to Santa Monica in the mid 1990s, the retired couple from Boston landed a two-bedroom unit on the third floor of the Princess Eugenia apartment complex in one of the coastal city’s prime locations.

For $1,145 a month, the couple settled down in the well-heeled Wilmont neighborhood, walking distance from Santa Monica’s bustling Downtown commercial district to the south and the Palisades Bluffs and beach to the west.

Under Santa Monica’s rent control law, the couple enjoyed a fixed rent for the 15 years they lived in their apartment. That is, until they were arrested by FBI agents in June 2011. Charles and Carol Gasko were actually the aliases of notorious mobster James “Whitey” Bulger and his companion Catherine Greig.

Three years after his arrest, the 84-year-old Bulger is serving two consecutive life sentences and Greig is serving eight years for hiding him. And, the apartment where the couple spent nearly two decades hiding out, with about $800,000 in cash and about 30 guns hidden in the walls, is back on the market.

The asking price? $2,725 a month, or more than double what Bulger and Greig paid for the unit.

While the circumstances under which the apartment’s former tenants vacated the unit may be a bit out of the ordinary, the apartment’s rising rent is a much more typical story in Santa Monica.

Santa Monica Politics and Rent Control

The rent control law has shaped Santa Monica’s political scene perhaps more than any other piece of the city’s charter.

In the mid-1970s, a group of young upstarts, many of whom had seen their friends evicted or forced out of town by spiking rents as new land owners like Donald Sterling sought to maximize profits from their recent investments, began organizing for better rent protections.

On April 10, 1979, Santa Monica passed one of the most stringent rent control laws in the country. According to the Rent Control Board’s website, “The law was intended to alleviate the hardship of the housing shortage and to ensure that owners received no more than a fair return.”

In a town where about 70 percent of residents rent, the new renters’ rights movement became a formidable political force organized around the then-ascendant group, Santa Monicans for Renters’ Rights, an organization whose endorsed candidates have enjoyed a majority on the City Council since the 1980s.

For about 30 years, there was a virtual freeze on all rents in buildings built before 1979 in the bayside city, since Santa Monica’s rent control law – unlike Los Angeles’ or San Francisco’s – didn’t allow vacancy decontrol, under which a land owner could raise rents between tenants.

During that time, in Santa Monica’s 28,000 rent-controlled units, one tenant would move out and a new tenant would move in, all the while the rent would stay the same.

Costa-Hawkins and the Weakening of Santa Monica Rent Control

While rent control still exists in Santa Monica, it is not as strong as it once was.

In 1999, a State law called the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, went into full effect, requiring Santa Monica and other similarly strict rent control jurisdictions, like West Hollywood, to allow land owners to raise rents when tenants moved out.

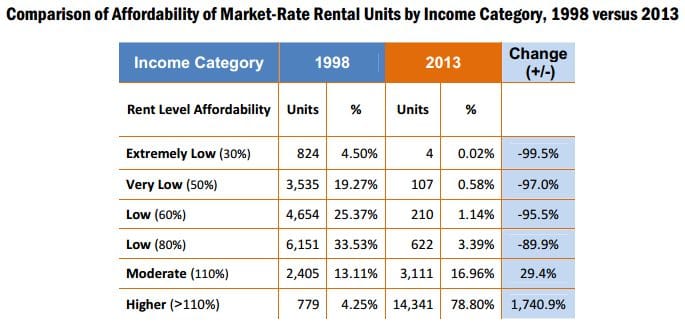

Vacancy decontrol has “been transformative on the affordability of rent‐controlled housing,” according to Santa Monica Rent Control Board’s 2013 annual report. “In the past 15 years, Santa Monica has been becoming a place where primarily only higher‐income households can afford to rent.”

According to that report, in 2013 only five percent of controlled units were affordable to a family of four making about $52,000 a year (or, 80 percent of area median income). In 1998, the year before Costa-Hawkins went into full effect, 83 percent of controlled units were affordable to a family making 80 percent of the area median income, according to the report.

Market Rents and Affordable Housing

While Bulger’s old apartment may rent for an artificially high price in part due to the notoriety of its former occupants, overall, rents in Santa Monica are higher than they have ever been, according to the Rent Control Board’s report and also anyone who has ever tried to rent in Santa Monica.

As we discussed in the first segment of this series, high market rate rents are impacted by several factors, including scarce land – Santa Monica is about eight square miles, much of which was built out in the 1970s – and zoning restrictions that limit construction to about 84 feet throughout most of the city.

Combined with a regional housing crunch and a high desirability factor – turns out, Santa Monica is a nice place to live – market-rate rents in Santa Monica are among the highest in the county.

While about 28,000 of Santa Monica’s 36,000 rental units are still under rent control, only about a third have seen no market-rate rent increase (the Rent Control Board allows land owners to raise the rent slightly to account for inflation) since the Costa-Hawkins law came into effect. The rest have seen at least one market-rate rent hike since 1999.

Still, rent control has its shortfalls when it comes to providing affordable housing to the neediest. As illustrated by the Bulger case, rent control units can sometimes be occupied by people who don’t necessarily need subsidized rents.

After all, he did have nearly a $1 million in cash on him, and who knows how much those guns were worth? And, if he hadn’t been caught, there is no telling how long he and Greig would have remained in that unit.

And, since rent control only applies to units built before the law went into effect, no new controlled units get built, except in special circumstances when developers are required to replace controlled units.

That’s why Santa Monica’s commitment to affordable housing extends further than just to rent control. In our next segment, we will take a look at the City’s Affordable Housing Production Program and the local nonprofits that help the city’s neediest renters.