This post, by Frank Gruber and Juan Matute, first appeared on The Healthy City Local.

We wrote in our last piece that although the City of Santa Monica is experiencing an unprecedented financial crisis during which revenues are predicted to miss targets by $200 million over the next two years, the City has substantial assets to use to cushion the impact of the crisis. In this post, we want to dive deeper into those assets and what might be done with them, but we also want to start with some words of caution.

For one thing, the data set forth in the latest Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR), which we cited in our post, are as of June 30, 2019. While the CAFR shows that the City had over $700 million in cash and investments, of which the report identified $171 million as unrestricted, one friend pointed out to us that these numbers did not reflect the $42 million settlement of the Eric Uller abuse litigation; presumably the ultimate source of that payment was the City’s accumulated assets. But this only highlights the need for the City Council to be aware of just what the City’s resources are before the council makes decisions about the budget.

In our post we said that the City needed to prudently tap its assets to “determine how much [could] be tapped over three or four years” to maintain necessary services. We want to say that we don’t know if the crisis will be over in four years. As Frank wrote a few weeks ago, we could easily be at a major historical inflection point, the end of the post-War era of worldwide economic expansion. Neither one of us is an economist (not that economists are particularly good at predicting), but it is plain that 2020 is just as likely to be another 1930 as it is to be another 2008. If not more likely.

Even if we are facing another Depression, it makes sense to use the City’s assets to cushion the impact over a finite term (say, three to five years), because that would give the council and staff enough time to restructure the City’s finances to accommodate a changed world. Further, to the extent the City can dispose of non-financial assets, those assets are likely to lose value over time if the economy tanks.

A changed world, with dramatically less travel, with less disposable income available for entertainment, with less demand for office space, would be brutal for Santa Monica. A full one-third of the City’s revenues come from hotel taxes, business taxes, and sales taxes; these are to a great extent generated by non-residents. The City’s assets will not save Santa Monica from having to reconsider its levels of expenditures and what it spends money on. The assets should, however, allow Santa Monica to make thoughtful, not-panic-induced choices.

Many of those choices, however, must be made in the next few weeks, at least those that affect the next fiscal year. The City Charter requires the City Manager to submit a draft budget to the City Council at least 35 days before the start of the fiscal year beginning July 1st (May 27). According to the staff report for the May 26 City Council meeting (two days from now), the proposed budget will be submitted as an information item at the meeting. The City Council will have hearings in June and it must approve a balanced budget by June 30. After the initial budget is passed future adjustments would require a supermajority of five votes. It is critical that the council, before voting on the budget, be aware of the assets that are available to soften the impact of the impending deficits.

So what are those assets?

As we discussed in our first piece, the City’s net worth on paper is $1.6 billion. Its assets include $437 million in federal securities, $178 million in corporate bonds, and $25 million in municipal bonds. A portion of these relatively liquid assets is needed to cover current liabilities, which totaled $108 million at the end of fiscal year 2019. But before approving the 2021 budget, the City Council needs to know to what extent these liquid assets can be drawn upon to fund current expenditures.

Looking ahead longer term, into a potential Depression, the City must evaluate what fixed assets it can dispose of to soften the transition to a budget structured for a new reality. In certain circumstances, the two goals can be joined. Restructuring government is not only a matter of cutting jobs; it should also involve a discussion about the purpose and goals of local government.

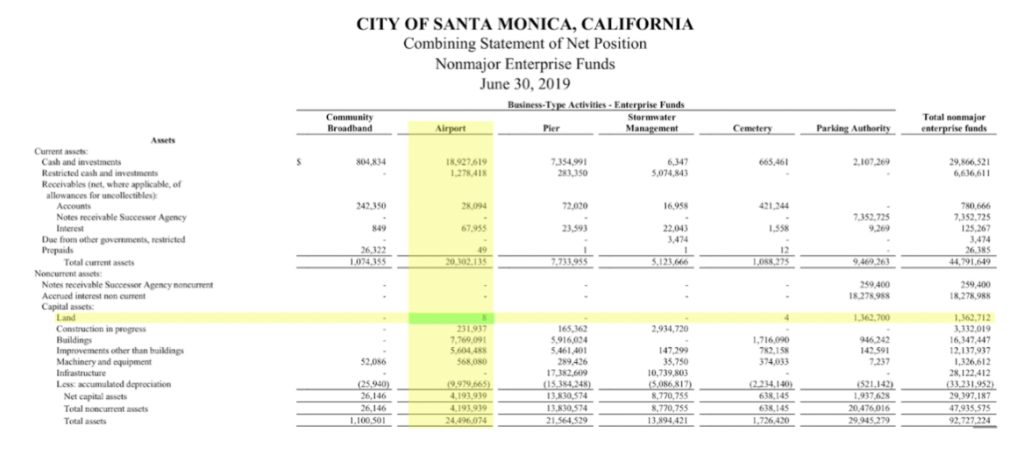

When it comes to the City’s real estate, the CAFR substantially understates the City’s position. As we discussed in the previous post, accounting rules require deduction of depreciation, which has no connection to market value. Even more significant, accounting rules require the City to list landholdings at what the City paid for the land. For instance, all the land at Santa Monica Airport is valued at eight dollars (yes, about two cappuccinos) in the CAFR. (Not that selling any of the Airport would help the City’s budget, since per the FAA the proceeds would have to be deposited in the Airport fund.)

While much of the City’s real property is dedicated to municipal purposes, and can’t be sold, the City needs to consider what services and “enterprises” are, or should be, part of the City’s mission.

For instance, in the 1950s “Republican-Socialists” who ran Santa Monica believed it was the City’s mission to subsidize local businesses by building a Civic Auditorium. Unfortunately, once built the Civic became a large drain on City revenues. The fiscal bleeding only stopped a few years ago when the City closed the Civic to the public on the grounds that it was seismically unsafe. At that time the City formed a task force (one of us, Frank, was on it) to figure out how to save the Civic as part of a multi-use development. But any realistic hope of such a fate for the Civic evaporated when the City Council approved a walled-in soccer field and a water runoff retention facility in the Civic’s parking lot.

Meanwhile, the staff report for Tuesday night’s City Council meeting calls for another $228,000 to be spent to maintain the Civic. Is owning a Civic Auditorium integral to the City’s mission in 2020? We don’t think so. We’d rather see $228,000 used for more productive purposes.

At $200 per square foot, a conservative valuation in Santa Monica, the four acres containing the Civic would be worth $35 million. Perhaps it is time to sell the property?

The City also owns many parking structures and parking lots. Municipal parking structures are assets of declining value in an era of shared ride apps and scooters and a future of automated vehicles. Given that City policy now is to discourage driving to fight Climate Change, would the City today choose to enter the parking business? The City should look into selling one or more parking structures downtown, including those at Santa Monica Place. The owners of the mall might be willing to pay a premium given that in the long run redevelopment potential for these sites is among the greatest in the city as they are in the Transit Adjacent Zone.

The City should also consider whether it should be in the development business. We’re thinking in particular of the fiasco at 4th and Arizona. It’s proven impossible for the City to make decisions when it is both the landowner and the regulator. It is time to sell that property. It would be valuable. A city-owned, 25-space surface parking lot in downtown Santa Monica sold for $6.2 million in 2018. Based on that, the much larger property at 4th and Arizona could be worth at least $100 million at its current zoning, and more if permitted to develop in accordance with the large site parameters set in the Downtown Community Plan.

The City also owns properties that it leases to commercial tenants who pay ground rent, sometimes at below market rents. Some of the city’s properties aren’t even in the City of Santa Monica. The City should determine whether the market values of these properties are greater than the present value of the future rents: it may be advantageous to sell. The City would receive a one-time infusion of cash by selling any of these holdings, either to investors or to the long-term land lease holders, which include the Windward School in Mar Vista, the Viceroy Hotel, and Kite Pharmaceuticals. Other properties the City owns are not developed, such as a parking lot near the City’s water treatment plant in West L.A. that is conservatively worth $15 million.

Even if the market for commercial real estate drops 20% from its recent peak, the City should be able to generate at least $80 million by selling just a portion of these properties, which generate about $4 million a year in land lease payments. We don’t know if a one-time infusion of cash in exchange for a perpetual reduction in lease revenues is prudent, but now is the time to explore such trade-offs.

Santa Monica can hope that future revenues exceed current projections. It can hope that a higher power (the federal government) grants it a proportional share of a proposed federal stimulus ($142 million). But if it needs cash, the City has substantial assets from which to draw. Santa Monica’s motto is “a fortunate people in a fortunate place”. We are indeed fortunate that the City has accumulated substantial wealth.

Thanks for reading.