The city of Santa Monica adopted a faulty plan when, in 2010, the Council unanimously approved the Land Use and Circulation Element (LUCE), the policy document that would guide the city’s future for the next 20 years.

The LUCE, the result of several years of community input, intensive planning, and thorough studies, is the roadmap for planning in Santa Monica. And that roadmap is wrong, endangering the future of our seaside city, the conservation of our precious natural resources, and undermining Santa Monica’s goal becoming water self-sufficient.

[pullquote align=left]

With California’s drought making headlines, no-growthers increasingly have begun invoking the issue of water availability as a talking point to argue for exclusionary housing policies.

[/pullquote]It’s a compelling narrative currently being shopped around to the city’s local neighborhood associations by members of the conservative no-growth group Residocracy in order to promote a plan to eventually put an initiative on the ballot that would, if it passes, limit all future projects in Santa Monica to three stories.

As compelling as the narrative is, however, it is also factually inaccurate.

With California’s drought making headlines, no-growthers increasingly have begun invoking the issue of water availability as a talking point to argue for exclusionary housing policies.

The crux of the no-growthers’ claim is that the small army of highly-skilled, professional urban planners who worked on codifying the LUCE, in fact, had gravely underestimated the amount of growth that would happen in Santa Monica when they projected water use through 2030 for the document’s environmental impact report.

They claim city planners had only anticipated that the city would grow by about 100 new housing units a year (about 186 people annually) through 2030.

As such, Armen Melkonians, the founder of Residocracy, said at his group’s most recent presentation Tuesday night before the Mid City Neighbors board, the LUCE is invalid, and so too would be the zoning ordinance update, based on the LUCE, that the Council will vote on this spring.

“Once the LUCE was adopted… developers started flooding Santa Monica with development applications,” he told the small group gathered in the conference room at the Colorado Center Tuesday night.

Citing a count he did in 2012, “in the two-and-a-half years… after the adoption of the LUCE, we had almost as many development applications as the projected growth for 20 years.”

The reality of the situation is something else entirely, however.

[pullquote align=right]

To put it simply, the political strategy of those who believe Santa Monica should be closed off to future newcomers is to cast doubt on the city’s plans for smart, ecologically sound growth, despite the fact that the plans have been vetted and approved at both the local and regional levels.

[/pullquote]

Myth: The LUCE is Faulty

In fact, the LUCE plans for about a 10 percent increase in population — or about 9,500 people and 4,955 new homes — in the 20 years from 2010 to 2030. That’s about three times as many new residents Melkonians claims were in the LUCE’s future growth projections.

“[T]he proposed LUCE accounts for 100 percent of all new development and land uses in the City and thereby encompasses the sum of all growth in water demand as well,” according to page 722 of the 2,000 page environmental impact report for the LUCE.

And, on page 554, the report reads, “[I]mplementation of the proposed LUCE would create additional housing opportunities in the transit corridors and at future Expo Light Rail station areas, including workforce and affordable units, resulting in the potential to add 4,955 housing units to the City‘s existing housing stock by 2030.”

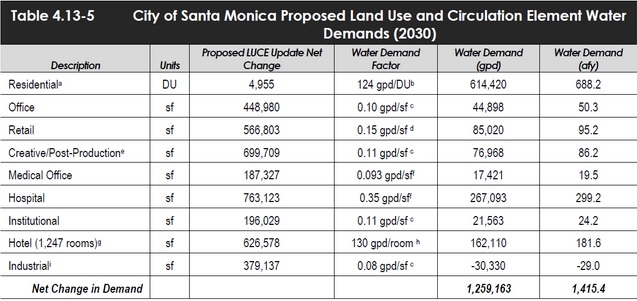

Santa Monica has been planning to accommodate that amount of growth and has studied the impact on all aspects of the environment that adding another 9,500 people to the city’s population over the next 20 years would have, including the amount of water the new households would use. Table 4.13-5 on page 714 summarizes this analysis.

Myth: Santa Monica Growing Faster than We Planned

While Melkonians’ numbers may be off, what about his claim that the alleged preponderance of development has already maxed-out the number of new housing units planned for in the LUCE? Are we really growing faster than we anticipated?

The short answer is, no.

It has been five years since the LUCE was approved and so city planners recently took a look back to see what has changed in Santa Monica.

According to the recently-released update on the LUCE [PDF], Santa Monica has actually seen the rate of growth slow dramatically since the document was approved.

The update shows that since 2010, 80 units regulated by the LUCE have been completed in five different projects.

There are another 346 LUCE regulated units in 11 projects currently under construction and 435 LUCE regulated units have been approved but haven’t yet gotten building permits.

So, Santa Monica is currently building about 172 units per year under the LUCE, but the LUCE plans for a rate of housing approval of about 248 units a year if the city were going to build all the 4,955 units projected in LUCE environmental impact report.

The report does note that while construction and project approvals slowed down in 2010, there were about 984 units in about 36 projects approved under the 1984 General Plan, before the LUCE was enacted. Some of those units were only recently occupied.

Still, Santa Monica is certainly not in danger of building more homes by 2030 than city planners anticipated. And, should there be more units produced than anticipated by the LUCE before 2030, it would require a further study by the city to look at the impact of additional units on the environment.

Myth: Growth Threatens Santa Monica’s Goal of Water Self-Sufficiency

Increasingly, no-growth advocates have cited the city’s water self-sufficiency strategy as an excuse to resist any new housing construction.

Santa Monica currently gets about 70 percent of its water from local wells within and just outside the city’s borders. The city pays to import the other 30 percent of its water from the Sacramento Delta and Colorado River through the Metropolitan Water District (MWD).

Using locally-sourced water is cheaper and has less of a negative environmental impact. That’s why Santa Monica has a plan to wean the city off imported water by 2020.

But, as the claim goes, how could we possibly get to be water self-sufficient by 2020 if our population keeps growing?

Simply put, we get better at using it more efficiently, through conservation methods and technological improvements that prevent wasting water.

Again, when the city studied projected population growth in the LUCE, it took into account the water self-sufficiency policy.

“To meet the City’s self-sufficiency goal to stop importing water by 2020, each person needs to reduce their water use to 123 gallons a day – a savings of 4,000 gallons, per person, per year,” according to the city’s website.

Those thresholds, however, aren’t based on a static population but take into account the growth projected in the LUCE, which is possible because all but four of the new homes the city anticipates will be built in Santa Monica will be multi-family dwellings, either apartment or condos, which are significantly more water efficient than single-family homes.

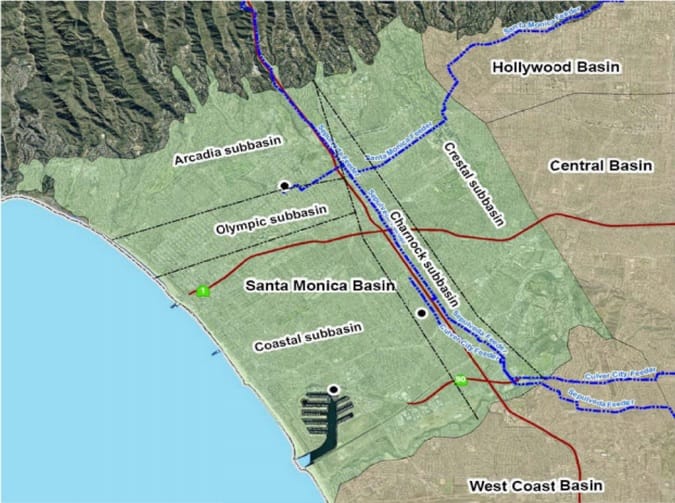

Santa Monica faces a challenge in managing its local groundwater, which comes from a basin not only under Santa Monica but also below Los Angeles, Culver City, and Marina del Rey.

While Santa Monica is currently the only city that extracts water from this basin, that may not be the case in the future.

In the world of water rights, the Santa Monica Basin is “unadjudicated”, meaning that no authority has yet to determine Santa Monica’s right to this water versus the rights of other communities.

While Santa Monica seeks to use local groundwater in order to be environmentally responsible and reduce the impact the city has on upstate delta ecologies, becoming self-sufficient also insulates the city from future supply disruptions for imported water, like an earthquake that splits the California Aqueduct.

Santa Monica would face competition if Los Angeles or Culver City think their imported water supply is vulnerable, or if they follow Santa Monica’s lead on impacting upstate ecologies. Thus, Santa Monica’s own water self-sufficiency is dependent on its neighbors’ water security.

With all but four of the 4,955 new homes planned as multifamily units, the LUCE enacts State and regional policies to make new users of water far more efficient than existing users, focusing new population growth in multifamily housing in water-efficient communities with a temperate climate rather than in vast developments of single family homes that forever reshape the hot and dry desert.

Santa Monica can — and should — add new homes in order to offset even greater water demand elsewhere in the region, but having a local source of groundwater is not a free pass to waste water.

The city must ensure that its local groundwater is sustainably managed so it can be a resource for future generations.

Take out too much water and a number of problems could happen, including the intrusion of salty seawater which would require the energy-intensive desalination of our groundwater.

The Politics of Doubt

To put it simply, the political strategy of those who believe Santa Monica should be closed off to future newcomers is to cast doubt on the city’s plans for smart, ecologically sound growth, despite the fact that the plans have been vetted and approved at both the local and regional levels. It is, in the strictest sense, impossible to predict precisely what the world will look like in 2030, just like I couldn’t say with 100 percent certainty that I won’t get hit by a car later today.

However, just as I won’t put the brakes on my career and stop paying rent because I can’t know for certain whether I’ll be hit by a car later, the city acknowledges that future growth will happen and Santa Monica is well-positioned to make sure it happens in a way as ecologically sound and environmentally sustainable as possible.

Santa Monica Next Advisory BoardMember Juan Matute contributed research and reporting to this article.