A recent post on the Wall Street Journal noted that White House economists have been wringing their hands over local land use policies throughout the country.

The problem, according to Jason Furman, chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, is that many desirable cities around the country have been driving up the cost of housing by using local zoning to block future housing growth. When those cities are major centers for quality jobs, like Santa Monica and West Los Angeles, restrictive zoning actually prevents people from being able to move near better economic opportunities. Furman’s remarks were made in a speech at an event hosted by the Urban Institute and CoreLogic and reported on by The Wall Street Journal and The Atlantic’s CityLab.

Over the last 30 years, coastal California cities, like Santa Monica and Los Angeles, have significantly restricted the amount of housing that can be built by limiting the height and density of new buildings, the consequences of which were well-documented by a Legislative Analyst Office’s report that came out earlier this year.

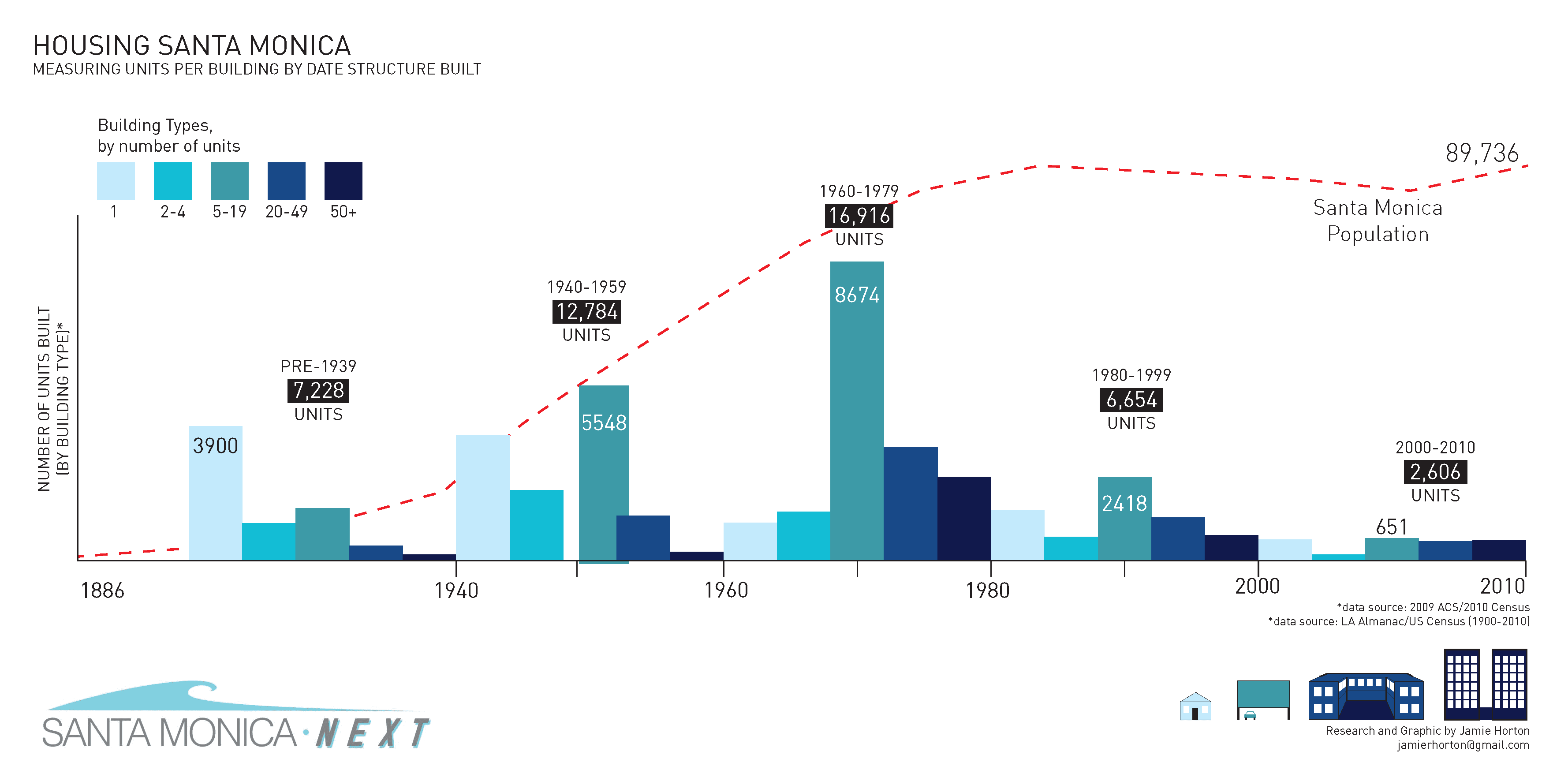

In 1980, for example, Santa Monica was home to 88,314 people. Today, it’s home to about 93,000 people. According to estimates by the California’s Legislative Analyst’s Office, L.A. County has underbuilt housing by about one million units during that time period, contributing to the region’s dubious distinction as California’s most unequal region.

While Santa Monica’s resident population hasn’t significantly increased in those years due to sluggish housing growth, the rents and home prices have increased dramatically, a result of decades of a “minimal growth” housing policy that continues today.

In that same time period, Santa Monica became a regional job center. Some estimates suggest that the city’s population doubles during work hours, but lack of new housing means most of Santa Monica’s workers are commuting in — usually by car — for work.

From the Wall Street Journal:

[O]ther cities make things worse with zoning and other land-use restrictions that discourage production, said Jason Furman, chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, in a speech Friday at a housing conference co-hosted by CoreLogic, a data company, and the Urban Institute, a think tank.

“Artificial constraints” on housing supply hinders mobility, and increasing mobility “is going to be an important part of the solution of increasing incomes and increasing incomes across generations,” Mr. Furman said. Zoning rules, of course, aren’t distributed randomly across the country, which means they’re “actually correlated with those places that have higher inequality,” he said.

The consequences are significant for those who want to live in a place like Santa Monica to have access to better, high-paying jobs: “This feeds a cycle in which cities that have more restrictions on land use have higher inequality, which further constrains mobility, which further exacerbates inequality, and so on,” the Wall Street Journal post reads.

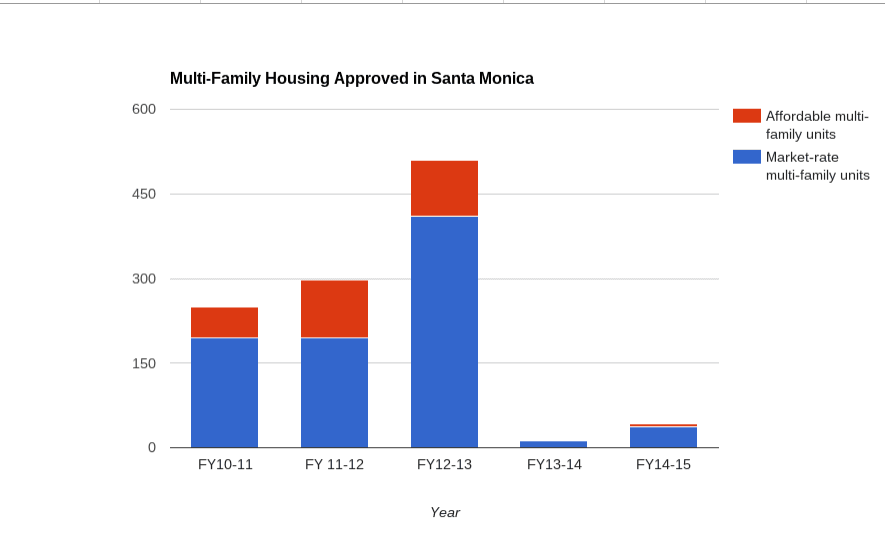

Like in San Francisco, as demand to live in Santa Monica has increased, the city has actually seen a decline in the amount of housing it approves recently as the city updated its zoning ordinance. The city is planning for about 5,000 new units to get built over the next 15 years. Yet the Council recently heard from staff that a minimum of 400 to 550 new subsidized affordable units a year alone need to be built in the city in order to maintain the current levels of affordability. That number doesn’t take into account the market-rate housing units that would also need to be built to house those who would not qualify for below market-rate rents.

The situation in Los Angeles and Santa Monica could potentially get even worse, as no-growth activist groups in both cities are looking to put measures on the ballot that would essentially freeze any significant growth by requiring most projects to go before voters.

While the White House is concerned about the impact of restrictive zoning on upward mobility and the economy, there is little the federal government can do, according to the Wall Street Journal. But, it is something that President Obama is “personally concerned about,” according to Furman