Agreed: ATP Is Key

At last week’s meeting of the California Transportation Commission, there was one opportunity for people to comment on the threatened cuts to the Active Transportation Program budget. The agenda item was about the 2023 Active Transportation Program Benefits Report, which uses a new tool to calculate increased travel by bike and walking and decreased crashes, injuries, and fatalities in California as a result of investments made in the 2023 Cycle 6 ATP.

There seemed to be strong agreement among commissioners, staff, and public commenters that the ATP punches above its weight in terms of climate, health, and safety benefits, and is a “key part of California’s climate efforts.”

Several callers emphasized the importance of the ATP beyond what is shown in the report. For example, callers from Butte, Shasta, and Nevada counties mentioned that rural areas and Metropolitan Regional Organizations alike rely on ATP projects to help them meet federally required emission reduction targets as outlined in their Sustainable Communities Strategies. “The timing… couldn’t be worse,” said Sean Tiedgen of the Shasta Regional Transportation Agency. “The budget has to be passed on June 15; Cycle 7 applications are due on June 17. There are many unanswered questions, and meanwhile cities and counties are spending millions of dollars to develop applications, with a large amount of uncertainty,” which raises project costs, he added.

Commissioners also commended the program. Commissioner Clarissa Falcon pointed out that its multiple benefits are what “excite us” at the CTC. “The program is fundamental to achieving [climate goals].”

“The ATP is a star program,” said Commissioner Hilary Norton. “This is often the first program where people get to know the CTC. And not enough is said about the hand-holding and assistance that CTC staff offer to applicants,” especially during COVID when cities needed longer timelines to apply but also needed funding to arrive on time.

Commissioner Adonia Lugo added that, as the benefits measuring tool is developed, other benefits should be measured as well – in particular jobs and employment benefits. “I would love to see the room we had yesterday [when labor organizations showed up en masse to support the project to widen I-80] in support of [ATP] projects,” she said. “There’s a sense of either/or, of cars vs. bikes, but I don’t think that supports the California we want to see.”

She also pointed out that the ATP is trying to achieve things that other projects don’t. “We are banking on behavior change [to meet our climate goals],” she said. “If we add a lane on a highway, people are going to drive. But with the ATP we’re trying to convince people to change their behavior – that’s hard. It takes programming.” She spoke of the diverse groups “that are thinking about active transportation and its effects on community. They get involved with us through the ATP. They are telling us they need more opportunities in funding and contracting. We have a real incubator in creating career pathways,” she said. “I would love to think through how do we make the connection here, so that when the governor looks at the budget he doesn’t see something that’s easy to cut.”

2023 Active Transportation Program Benefits Report

The report presented to the commissioners sums up ATP investments’ projected benefits for safety, climate, air quality, and public health. Dillon Fitch from the Davis BicyclingPlus Research Collaborative at UC Davis worked with the Active Transportation Research Center and CTC staff to develop the tool, which is still a work in progress, but “it’s better than anything we’ve had before this,” he said. It uses existing travel demand models and bases its calculations on academic research to estimate the effects of new facilities on factors such as route substitution and mode switch. This facilitates predicting increases in biking and walking and decreases in miles driven, for example.

The 2023 program will build 53 miles of Class I bike path (off-street), 82 miles of Class IV separated bikeways (“protected bikeways”), 103 miles of Class II bike lanes (on-street). It will also mark 86 miles of Class III bike routes – though these are mostly ineffective, unsafe sharrow markings.

In addition, the 2023 program will result in 103 miles of new sidewalks, 52 miles of sidewalk improvements, 57 miles of multi-use trails, and 19 miles of “bicycle boulevards” (traffic-calmed streets). It will build 6,386 new crosswalks and about 70 new roundabouts, which can encourage more biking if the bike portion is well designed and safe.

The Benefits Report calculates that these 2023 projects will reduce driving (VMT – vehicle miles traveled) by 319 million miles, and increase the number of miles traveled on bike by almost 500,000. They calculate a reduction in the number of crashes on streets and roads by 6,000, with 5,500 fewer traffic injuries and 223 fewer fatalities. They also project reductions in fuel consumption (by 3.9 million gallons), greenhouse gas emissions (by 44,500 metric tons), and particulate matter (PM2.5) (by 2.76 tons).

There are shortcomings and gaps in the tool – a major flaw being that it hasn’t been able to measure the effects of off-street paths, which may be the best ATP projects with the highest potential for increasing biking and walking. The tool also produces a range of effects, and uncertainties in the data can increase that variability. But uncertainty is not unique to this particular travel demand model. Highway proponents use models that make highly quantified but demonstrably false predictions regarding impacts on congestion, pollution, and safety. This new tool acknowledges its uncertainties and ranges, providing a refreshing transparency compared to highway builder hubris.

The team will continue to develop and refine the tool, its inputs, and its measurements, and as more ATP projects get built and measured – and as more passive bike and pedestrian counters gather better data – results will solidify over time.

The Funding Issue

One of the ATP’s goals is to encourage cities and counties to develop the best bike and pedestrian infrastructure and programming possible. But to do so will require an ongoing and stable source of funding – something that the state’s transportation budget has, unattached to what happens with the general fund – but the ATP itself does not.

The 2023 Active Transportation Program Cycle 6 was bigger than any previous cycle, because it received a one-time “augmentation” from the state’s general fund of about $1 billion. The CTC requested that extra funding, made possible by that year’s budget surplus, at the suggestion of former CTC Commissioner Bob Alvarado, who admitted that his larger motive was to prevent the growing calls for more ATP funding to affect highway funding. Regardless of motive, that extra funding allowed the program to support more than three times as many projects in that cycle.

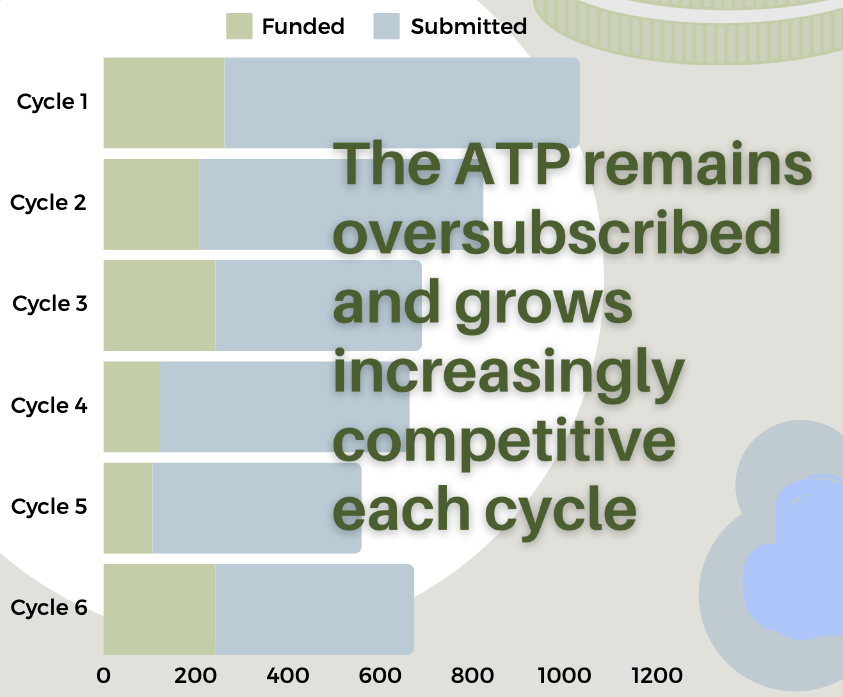

Even so, there were far more projects vying for that funding. The consistently oversubscribed program received 456 project applications that year, and was only able to award funding to 241 of them, across 41 counties. Without the extra funding, there would only have been enough money to fund 79 of the projects that applied.

But the fate of Cycle 7 is uncertain right now. None of the commissioners suggested sending a resolution to the governor to increase the program’s funding, let alone keep it at its current level. Nor did any of them suggest requesting a shift of funds from the State Highway Fund, a solution used to keep the ATP whole last year.

Some legislators are supportive – but all of them could benefit from hearing from their constituents about how important this program is.