The following article first appeared on Streetsblog California.

The California Bicycle Coalition held a lively discussion this morning on the topic of S.B. 960, the Complete Streets bill authored by Senator Scott Wiener. The webinar was a preview of the kinds of discussions that will happen next month at CalBike’s biannual Bike Summit, this year taking place in San Diego from April 18 and 19.

While a previous version of the bill, 2017’s S.B. 127, passed every legislative vote it faced, it was ultimately vetoed by the governor. Newsom said the bill was unnecessary because Caltrans already had a policy in place to accommodate the safety of all road users, and was supposedly moving away from its car-centric focus. Senator Wiener told the webinar attendees that at the time Newsom told him Caltrans’ “new leadership” needed the chance to make improvements on their own.

“Since then, there have been improvements,” said Senator Weiner, “but not nearly enough and not fast enough.”

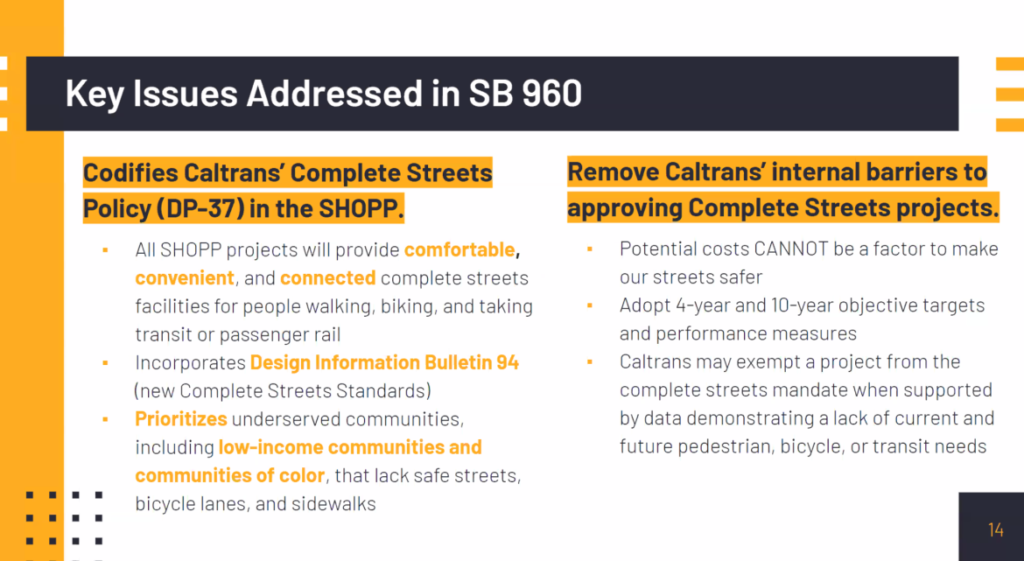

CalBike analyzed internal documents from Caltrans to better understand why this is so. “Decision documents,” used for projects in the State Highway Operations and Protection Program (SHOPP – the biggest source of road maintenance money in the state), explain why the department exempts projects from its own requirements to build “comfortable, convenient, and connected facilities for all users.”

“They frequently say that it’s too expensive, or it will slow down the project, and therefore they decide to exempt the project,” said Jeanie Ward-Waller, until recently Deputy Director of Planning and Modal Programs at Caltrans and one of today’s panelists. “We are not seeing the commitment we would expect to see,” she said.

“Caltrans is a black hole; it’s very hard to gauge their process from the outside,” said Sandhya Laddha from the Silicon Valley Bicycle Coalition, who talked about the campaign to transform El Camino Real on the San Francisco peninsula into a more livable, safer street. Caltrans has “great staff, but their hands can be tied by policies or direction from leadership,” said Laddha.

There is a plan afoot to repave about half of the 41-mile route, a state highway that passes through nineteen jurisdictions, cutting through several downtowns and business corridors as well as dense neighborhoods and past several schools. This is a perfect opportunity to move the project towards being a safe place for walking and biking and transit.

But “none of the agency actions” so far address complete streets. “If there is limited road width, the first thing that gets cut is the bike lane,” said Laddha. “If there is extra width, the first thing they allocate that to are wider lanes. They won’t add a pedestrian crossing if one doesn’t already exist.”

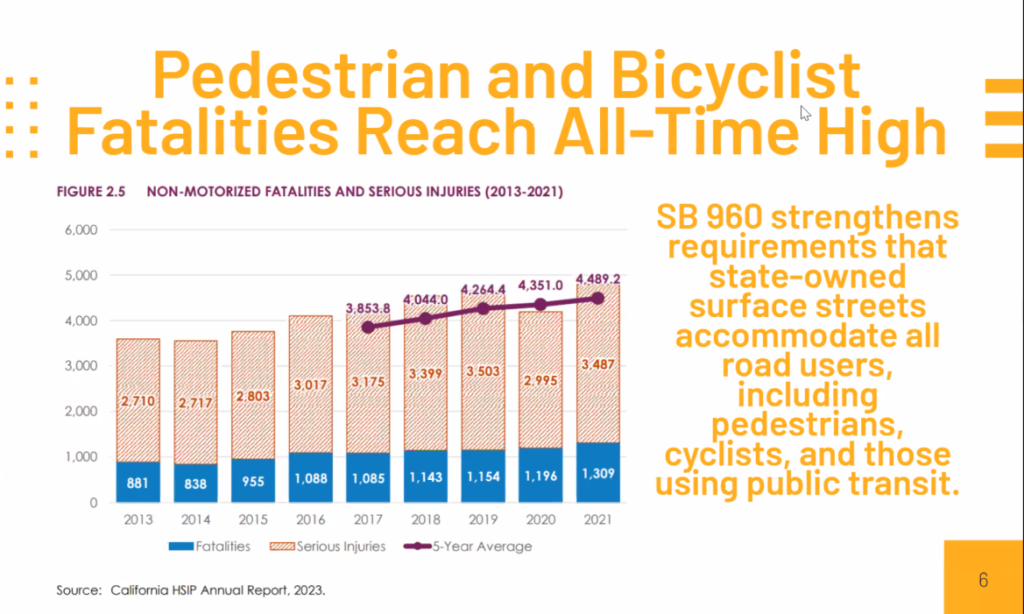

CalBike found that from 2022 to 2024, the rate of implementation of complete streets elements in SHOPP projects actually decreased, and that only 21 percent of them include bikeways, sidewalks, or crosswalk improvements, and fewer than ten percent of them included transit improvements. They also looked at proposed SHOPP projects over the next four years, and despite an identified $15 billion in needed investment, CalBike only found about $280 million in planned bike, pedestrian, and transit investments in the next four years. Only about twenty percent of SHOPP projects include any complete streets elements – including the most basic things like sidewalks.

“This is in a program that is going to invest over $20 billion over that time,” added Ward-Waller.

S.B. 960 would codify Caltrans’ complete streets policy, using its own language, which Ward-Waller said is “great – let’s support that in law.” It would require the department to apply its own design standards, and removes specific barriers to doing so. It would require the department to come up with four- and ten-year investment targets, and narrow the criteria for any exemption. That is, cost alone would no longer be a justification for not complying with the policy. Also, if Caltrans has plans that call for compete streets elements – and every district now has a Complete Streets plan – then they can’t just leave them out.

S.B. 960 focuses on Caltrans-controlled highways, many of which are main streets and major roadways in urban and rural areas. Transit operates on many of them, and in order to improve transit and increase ridership, those Caltrans-owned roads need to be improved with transit in mind.

“Transit priority has many advantages,” said Laura Tolkoff of SPUR. “It can improve the rider experience, improve safety, reduce conflicts, and reduce operation costs. It can help improve transit coordination, which is key to increasing ridership. It is also important for equity.”

“But progress has been slow; this has not been a core part of Caltrans’ highway operations,” said Tolkoff. “It is a complex organization. Adopting transit priority requires strong leadership and coordination. It requires Caltrans to adopt its own transit priority policy, setting performance targets, removing internal barriers to local transit priority projects, creating design standards, streamlining their own internal review process.” These are also part of S.B. 960.

“This bill is technical, but it’s also human,” said Tolkoff. “In many cases, these questions are a matter of life and death.”

All of the speakers reiterated that the point of S.B. 960 is, in the end, to make it easier to build and maintain safer roads for everyone. Senator Wiener described a long drawn-out fight earlier in his career to get Caltrans to make some straightforward changes to a left-turn signal on 19th Avenue in San Francisco. They kept refusing and delaying, until someone was killed there.

“It shouldn’t take fighting. It should not take someone dying,” he said. “It should just be baked into the DNA of Caltrans. They should just automatically be asking: how do we make this project safe for bikes, for pedestrians, for people waiting for the bus? That’s our goal.”

The panelists urged people to reach out to their representatives and to Governor Newsom’s administration to urge support for the bill, which will be heard in the Senate Transportation Committee on April 9.

CalBike also asked people to share their own stories about how they are impacted by the lack of street safety, and to send them examples of where there are unmet needs.

Senator Wiener spoke of what he learned in the process of running the previous bill. “Okay, I’m a city slicker guy,” he said. “I’m talking about how we’re fighting Caltrans about all these big roads. But in rural California, sometimes the only road in town is a state-owned road, and it may have no crosswalks, no sidewalks. One woman who testified last time around said even though her kids go to school a few blocks from her home, there was no way to safely cross the street, so she has to drive them there. That’s outrageous.”

The members of the Senate Transportation Committee, many of whom are likely to support the bill, would benefit from hearing from their constituents who support it. They are: Senators Dave Cortese (D-San Jose) Chair, Roger W. Niello (R-Fair Oaks), Vice-Chair, Benjamin Allen (D-Santa Monica), Bob Archuleta (D-Pico Rivera), Josh Becker (D-Menlo Park), Catherine Blakespear (D-Encinitas), Brian Dahle (R-Bieber), Bill Dodd (D-Napa), Lena A. Gonzalez (D-Long Beach), Monique Limón (D-Santa Barbara), Josh Newman (D-Fullerton), Janet Nguyen (R-Huntington Beach), Anthony J. Portantino (D-Burbank), Kelly Seyarto (R-Murrieta), and Thomas J. Umberg (D-Santa Ana).