The following article first appeared at Streetsblog Los Angeles. Read part 1, here.

Back in 2020, the climate was overheating in the form of large wildfires, intense hurricanes, and receding ice (all of which have since worsened). After a seven-year rulemaking process, Caltrans began requiring freeway builders to do something to mitigate additional driving induced by freeway expansion. Metro had dozens of L.A. freeway expansion projects underway and in various stages of planning and approval. What did Metro do? Start mitigating? Pause highway widening? Retool projects to be truly multimodal? Or just study the issue?

Metro opted for the study. In July 2021, Metro secured a $700,000 Caltrans Sustainable Communities grant to study how L.A. County freeway projects could mitigate the additional driving they cause. This is a bit duplicative, because the state already took seven years to produce extensive statewide guidelines on mitigation. But Metro said it would build on that work, and come up with L.A.-specific stuff.

Metro wasn’t alone; lots of other places called in consultants to study VMT mitigation, including Contra Costa County, San Diego, San Jose’s Santa Clara County, Santa Cruz, and probably others. (Many CA cities, including Pasadena and L.A., prepared for the 2020 VMT shift by doing studies in advance.)

At last month’s board meeting, staff briefed the Metro board on the progress of its VMT Mitigation study [staff report, project page]. This was the first public briefing on this study.

Metro has been meeting with stakeholders and gathering input. Unfortunately, they seem to be working mainly with a rogue’s gallery of pro-freeway-widening stakeholders. According to a May presentation, those team members include:

- 1) Automobile Association of America – which fought and is still fighting numerous initiatives for safer streets, public health, clean air, etc.

- 2) Gateway Cities Council of Governments – which supported Metro’s widenings of the 5 Freeway, 91 Freeway, 605 Freeway hot spots, and more.

- 3) I-5 Consortium Cities Joint Powers Authority – which supported and supports capacity expansion on the 5 Freeway.

- 4) North County Transportation Coalition – currently pushing Metro to widen the 14 Freeway.

- 5) Ports of L.A. and Long Beach – which supported Metro South 710 Freeway widening.

- 6) San Gabriel Valley Council of Governments – currently managing Metro’s widening of the 57/60 Freeway interchange.

- 7) South Bay Cities Council of Governments – which approved current and future Metro 405 Freeway widenings.

These folks probably aren’t tracking Metro’s VMT mitigation project out of concern for the climate. To Metro’s credit, there are two environmental organizations on their team: Climate Resolve and Natural Resources Defense Council.

Meanwhile Metro speaks out of both sides of its mouth on VMT mitigation.

Even when Metro’s own reporting shows that its highway expansion projects are harming the climate more than all its combined transit investment are helping, the July staff report praised increased driving while casting doubt on mitigation:

Staff seeks to balance the economic, access, and mobility benefits of increased VMT with the intended Program outcome of reducing VMT burdens, including emission of air pollution, collisions, and a built environment that can feel hostile for people traveling by non-auto modes.

Metro asserts that more driving brings “economic, access, and mobility benefits,” while aiming to reduce driving “intends” to lessen burdens such as “hostile feelings” experienced by Metro’s own bus riders. Rising traffic deaths are just “collisions.” The climate crisis – the reason that California now requires VMT reduction – is just “emission of air pollution.” (No mention of homes and other sites Metro demolished and continues to demolish for increased VMT.)

The presentation [video – starting at 2:02:00] was sort of a good cop/bad cop performance, with Metro Transportation Planning Manager Julio Perucho appearing to build a case for Metro not complying with Caltrans requirements, and Transportation Planning Senior Manager Paul Backstrom praising the sorts of multimodal projects and programs that could emerge.

Perucho spoke favorably of discredited car-centric Level of Service measurements (which Metro has long used to justify widenings) and bemoaned Caltrans “choosing” VMT as “an unfunded mandate” and “unfunded obligation” that saddled Metro with “additional financial liabilities.”

Perucho implied that Metro might not need to change its massive freeway widening project portfolio status quo because of “a very simple concept: that Metro has reduced VMT through our ongoing multimodal Measure R and M investments.” The implication is that, through some back-fill accounting trick, Metro might be able to just count its current transit expenditures as VMT mitigation, and not have to meaningfully change its freeway expansion.

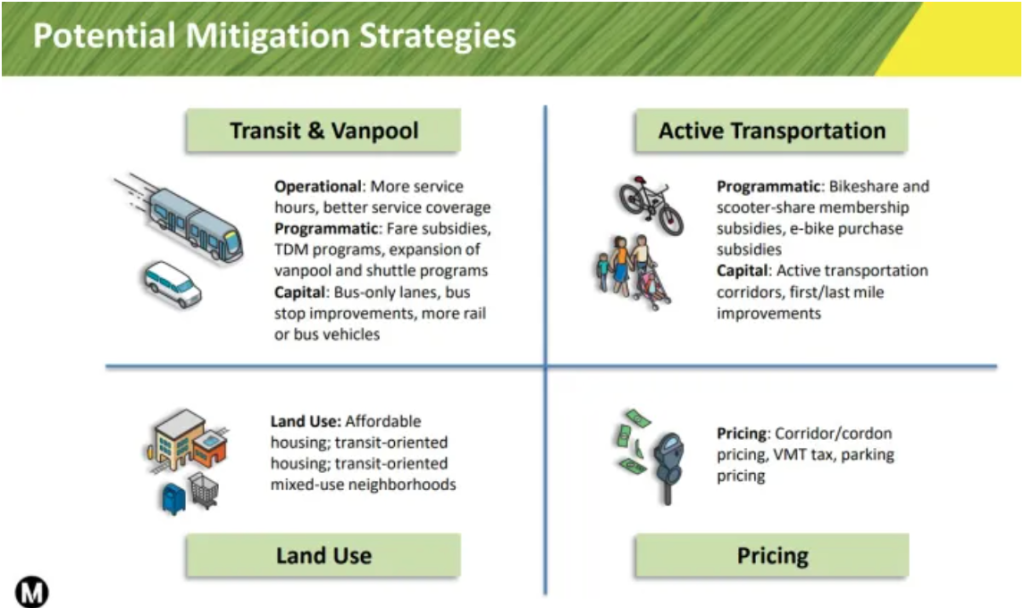

Backstrom, on the other hand, called Metro’s VMT study “a creative opportunity” for improvements like “increased transit service frequency, bus-only lanes, first/last mile improvements, TDM [transportation demand management] programs, affordable housing, [and/or] pricing strategies.”

Metro board reaction was similarly mixed, with the newest boardmember, City Councilmember Katy Young Yaroslavsky, affirming a VMT mitigation program as “our biggest opportunity to cut climate pollutants.” She noted that “passenger vehicle trips are by far the biggest source of GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions in the state, and the region is no exception.” (Tailpipe emissions are nearly half of L.A. GHG emissions.) She questioned why the program has taken so long to get started.

Yaroslavsky praised Metro’s pivot to South 710 Freeway multimodal improvements. County Supervisor Hilda Solis praised Metro’s turnarounds on South and North 710 Freeway expansion, and backing off of hundreds of planned demolitions along the 5 and 605 Freeways. (Note that none of these begrudging turnarounds stemmed from the goodness of Metro’s heart. All were the result of sustained community resistance, which forced Metro and Caltrans to reluctantly scale back deeply harmful freeway mega-projects.)

Glendale Councilmember Ara Najarian and County Supervisor Kathryn Barger were more skeptical about VMT mitigation, especially in car-centric, largely-suburban North L.A. County (where leaders prioritized Metro’s current $679 million 5 Freeway widening, and have routinely shifted transit funding to street and road projects). Barger cautioned that one-size-fits-all VMT mitigation could impact her sprawling district.

Najarian characterized North County residents as “challenged” because “they do not share in the benefit of much of the transit” Metro is building. Najarian then asked staff:

…I know that we’re planning some improvements on the SR-14. We believe that they are clearly identified as safety improvements. But in any event, there’s some concrete that’s going to be laid to increase some travel lanes, so would a proper mitigation of that be increased service upon the Metrolink lines to the Antelope Valley?

Staff affirmed that Metrolink commuter rail improvements would work. Then Najarian asserted that there are only two choices: “really it’s either the SR-14 or the Metrolink that serves that community.” Najarian gets most of the picture, but omits buses, walking, bicycling (which parts of North County do well and plan to do better), and even first/last mile connections to Metrolink.

Najarian and Barger’s implication seems to be that VMT mitigation is unfair to suburban communities (which have largely resisted transit improvements) because those communities have few choices other than driving.

The reality is almost the opposite: suburban communities are contributing heavily to the climate crisis because people there drive so much. The lack of viable safe mobility choices is a problem that meaningful VMT mitigation (such as frequent transit, bike-share, etc. – as well as Metrolink) would help solve. If the planet is to survive the climate crisis, then relatively well-off places (nations, cities, neighborhoods) which cause disproportionately high emissions (in large part due to driving, with higher per capita VMT) must carry their share of emission reduction measures.

What would meaningful Metro VMT mitigation look like?

Meaningful mitigation is outlined pretty well in Backstrom’s presentation (see slide above): do stuff that increases transit, walking, and bicycling – including increasing tranist-oriented affordable housing. This can include both capital expenses (such as new buses) and operating expenses (such as more frequent bus service, or even programs like fareless transit).

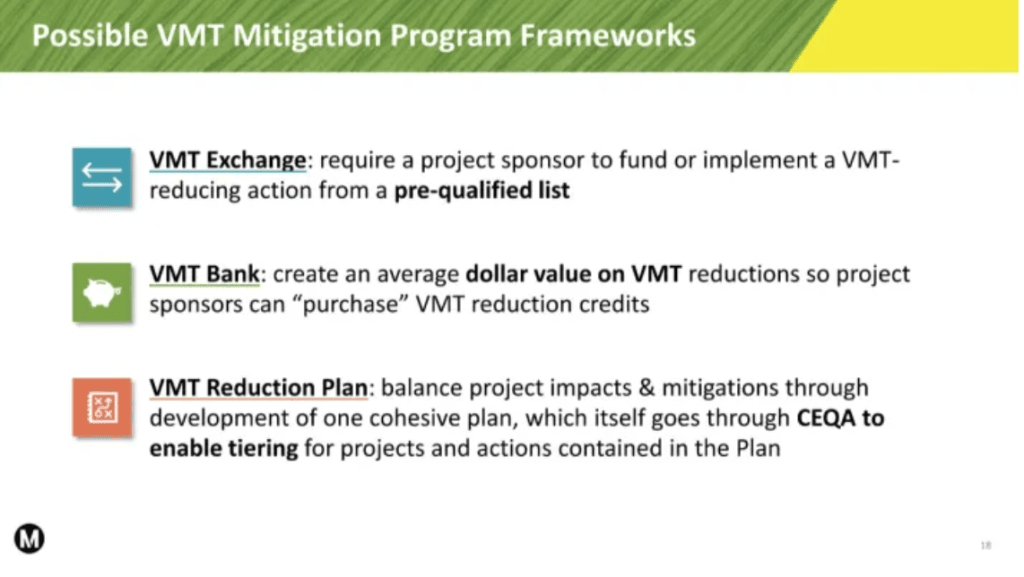

And because doing project-by-project mitigation is complicated and could slow down some freeway expansion, Metro is studying some mitigation banking models.

VMT banks or exchanges could streamline project delivery, which is a double edged sword. That is, Metro could use highway funding to accelerate VMT reduction programs (such as increasing bus service) right now, and stockpile those credits for later VMT increase projects.

These sorts of mitigation bank mechanisms can have geographic distribution problems. If, for a hypothetical example, Metro widens a freeway through working class Compton then mitigates that by adding a bike path in a higher-income part of Whittier, then impacted low-income communities would continue to bear project burdens while seeing few benefits. Metro is looking to balance things geographically by mitigation banking within sub-regions – but note that Compton and Whittier are both in the same Gateway Cities sub-region.

The effectiveness of Metro’s future VMT program will be in the details. As noted, where does mitigation take place? Also: how is VMT measured – for both freeway capacity expansions and for mitigation projects? How is it funded? More information on this is expected next month when Metro staff will present more detail on Metro’s mitigation study.

One way to look at how seriously Metro is taking VMT mitigation is to see how much money they plan to spend on it.

And where that money is coming from.

If Metro is consistent with its current and past practice, then Metro VMT mitigation funding would come from Metro’s highway budget. Fair is fair. When Metro transit projects were required to mitigate impacts to drivers (including bus rapid transit BRT and rail projects adding grade separations and widening/extending roads) those were paid for with Metro transit dollars. So now, since VMT mitigation is needed as a result of freeway expansion projects, highway program funds should flow to transit.

As Perucho stated, real mitigation will mean real “additional financial liabilities.” Did the Metro highway builders expect that they could just label highway expansions “multimodal” and not have to change the project scope? That’s what Metro has done – but doesn’t Caltrans’ 2020 requirement change that?

Honest effective mitigation could roughly double the cost of Metro highway widening projects.

It will be telling if Metro, as part of some sort of mitigation bank, starts tracking down every penny the agency spent on a bus since 12:01 a.m. on July 1, 2020 (when VMT mitigation requirements started), then tries to count all these earlier efforts as offsetting future freeway widening.

If Metro is going to be consistent, though, they should grandfather in – meaning not count – all VMT benefits of projects that began environmental clearance scoping prior to 2020 (clearly including all Metro rail and BRT operations). Caltrans required mitigation for VMT-generating projects that began scoping after July 2020, so VMT-mitigating projects should be treated similarly. Fair is fair.

This may be part of the study, but VMT mitigation should also be tailored to different parts of the county. As Supervisor Barger noted, it shouldn’t be one-size-fits-all – but not quite the way Barger expects. Projects in suburban areas of the county should probably do more VMT mitigation than central areas.

Many site-specific VMT calculators (including L.A. City’s) use trip data to show how location influences VMT. For a non-transportation facility example, it’s fairly intuitive that if a developer builds a ten-unit project at the edge of a city, it would generate more driving trips than a ten-unit project in the middle of that city (where transit, walking, and biking are more viable, but also where car trips cover shorter distances).

This sort of site-specific analysis could potentially put L.A.’s North County on the hook in two different ways. If they plan to widen a congested suburban freeway where few alternatives exist, then there’s a lot of guaranteed induced driving to mitigate for (each dollar spent widening North County freeways perhaps generates more VMT than in other parts of the county). And the mitigation dollars probably don’t go as far, because getting people who don’t typically ride transit onto buses there could be more expensive – so each mitigation dollar spent on North County transit probably mitigates less VMT than in other parts of the county.

There are a lot of factors that influence VMT, and SBLA may be overestimating or underestimating what shapes North County travel patterns. Hopefully Metro is studying these sub-regional differences and will hone its future VMT program accordingly.

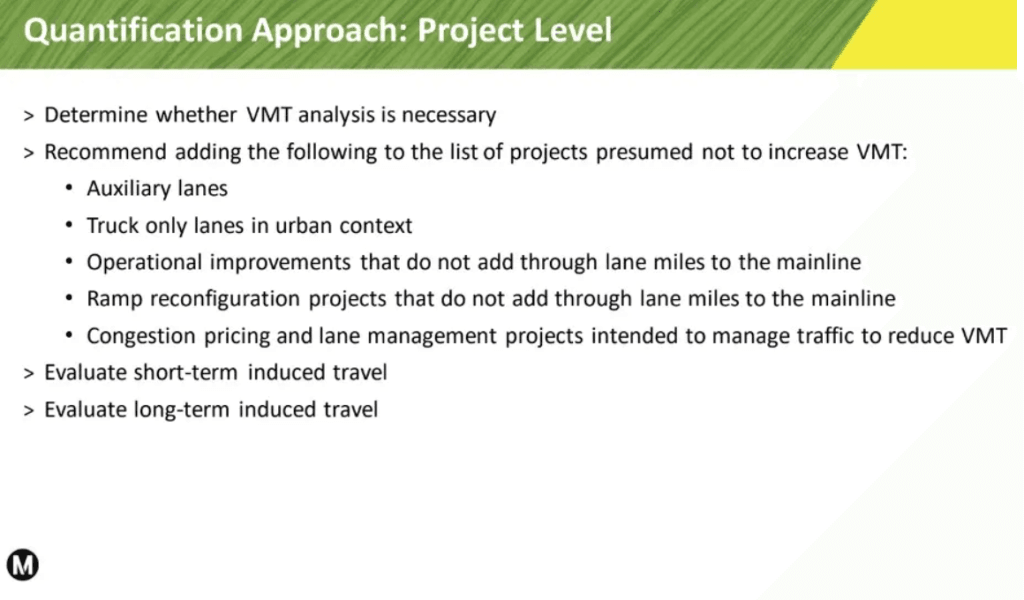

Another factor to look at is what projects Metro exempts from VMT mitigation. As noted in part 1, Metro and Caltrans are continuing to approve smaller freeway expansion projects (mostly under a loophole that allows piecemeal widening via short “auxiliary lanes.”)

Metro loves its auxiliary lane loophole and appears to be looking to bust it wide open so even more projects can go through. Currently, under state rules, the loophole applies only to an “auxiliary lane of less than one mile in length.” Metro’s VMT study is recommending that the following freeway expansion projects be “presumed not to increase VMT:”

- 1) auxiliary lanes [with no length specified – so Metro could add miles of new freeway lanes, and as long as they don’t go past an off-ramp, they are presumed not to induce VMT]

- 2) truck lanes [getting trucks out of shared lanes frees up those lanes for more driving]

- 3) operational improvements [a vague term Metro staff use frequently to describe freeway capacity expansion projects]

- 4) ramp reconfiguration projects [Metro and Caltrans never “reconfigure” on-/off-ramps to decrease capacity. These projects widen ramps and connecting roads, and that widening means more lanes, more driving, more VMT. Additionally, all of Metro’s current ramp reconfigurations – the 605, 60, etc. – are intended to make space for further freeway widening. Imagine if Metro were to, for example, split off utility relocation or bridge construction designed for a rail project, and then say “this utility relocation on its own doesn’t increase rail.” It would be laughable. The same is true for Metro ramp “reconfiguration” except that it both increases car capacity, and supports future increases.]

- 5) congestion pricing and lane management projects [There may be some genuine projects – like converting a general purpose lane to a toll lane – that actually reduce VMT and might appropriately avoid mitigation. But today, Metro mega-projects add multiple general purpose lanes, aux lanes, and express lanes together. The presence of a managed lane should not be a fig-leaf that exonerates other unmanaged expansion.]

For years Metro’s highway builders have been pushing lots of these smaller “early action” type freeway/ramp/road widening projects because they increase capacity a bit while teeing up later massive capacity increases. Now that Metro is required to mitigate these, staff turn around and assert “this isn’t capacity expansion – it’s just: operational improvements/aux lanes/ramp reconfiguration/safety/etc.” But if these weren’t increasing capacity, Metro highway builders wouldn’t be interested in them.

Lastly, Caltrans will need to continue to play a hugely important role in holding Metro to meaningful VMT mitigation. Though Metro acts like it owns freeways, Caltrans actually owns the state highway system, and has the last word on Metro freeway project scopes and environmental clearance.

Will Caltrans look the other way while Metro puts its thumb on the scale – perhaps low-balling project VMT projections, and/or accepting ineffective VMT mitigation? Or will Caltrans hold Metro’s hand to craft truly meaningful mitigation?

For a long time, Caltrans was arguably much more pro-freeway-widening than Metro. With legislative and leadership changes at the top, Caltrans has stepped back from widespread capacity expansion. In 2020, then Caltrans Director Toks Omishakin stated that his agency should be moving away from automatically widening busy highways.

Lately Metro staff have been critical of Caltrans for not wholeheartedly supporting Metro’s freeway widening. Former Metro highway chief Abdollah Ansari repeatedly criticized Omishakin and other Caltrans leadership for canceling the 710 expansion. Caltrans declined Metro’s request for a support letter for 57/60 widening, noting it didn’t align with Caltrans climate and equity goals. Last month, Perucho disparaged Caltrans “choosing” VMT for highway projects.

It looks like Caltrans leadership is needed again right now. Please, Caltrans, if Metro isn’t willing to align projects to serve your climate and equity goals – and your mitigation requirements – tell Metro that they don’t get to build in your rights-of-way.

What next?

Metro staff will present more details about the VMT mitigation program to the board next month, with program approval expected in Spring 2024.

The VMT mitigation program is likely to be a litmus test for Metro’s commitment to a habitable climate. Will the mitigation skeptics water the program down to opaque meaninglessness? Or will the agency take advantage of the program to pivot toward sustainability and equity? Or – most likely – will it be muddled middle ground?

Metro CEO Stephanie Wiggins has stated that climate action is among her priorities. While she has made some moves to curb the worst excess of Metro freeway widening including mostly ending mass home/apartment demolitions, there’s a lot of change still needed. VMT mitigation could help Wiggins’ Metro make good on its multi-modal promises to voters, by truly re-thinking its approach to highway expansion.